Dear readers, I hope you are having nice holidays. I’m taking this week off from writing new articles for you; I will resume next Sunday as usual. In the meantime, please enjoy this piece from the archives, enhanced with links for you to listen to theremin music and learn more about it. It is perhaps a fitting segue from last week’s article about UFOs, since the theremin is especially known for its presence in the soundtracks of The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Thing From Another World and It Came From Outer Space, among others.

The piece is adapted from an essay in my book For The Curious.

"I just bought For The Curious and can't put it down...except to write to you..."

–composer/arranger Anne Phillips, Founder of The Jazz Nativity

MAYBE YOU'VE NEVER HEARD of Professor Leon Theremin. But you have, for sure, heard his Frankenstein's monster of a musical instrument. Like the saxophone (named after Adolphe Sax who invented it in 1846), the theremin bears the name of its creator. The theremin is a rectangular-ish box with two antennas, one on either side. It is purely electronic. The oscillators within the box create a tone whose pitch can be manipulated with one hand as it moves around the antenna, and its volume with the other hand. The theremin is the only instrument that is played without actually touching it!

When I was around ten, a woman came to my school to demonstrate the theremin during an assembly. Lucky me–I was chosen to go up to the stage and give it a try! The screeches that I produced were a fairly accurate, if unintentional, musical portrait of Feeding Time at the Zoo. Playing the theremin was like trying to put a leash on a giraffe and take it for a walk. In my reverie, I fantasize that the woman who came to my school with the theremin might have been the great virtuoso Clara Rockmore. Her ability on this instrument is legendary. Moreover, Rockmore had studied with Professor Theremin himself.

Leon Theremin, born Lev Sergeyevitch Termen in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1896, had been living in the United States since 1927. He was inventing electronic musical instruments (sponsored by a wealthy patron), and had married his second wife, Lavinia Williams, a member of the American Negro Ballet. What did they have in common, the professional ballerina and the eccentric Russian inventor? Their marriage was not to last, but not for the usual reasons: in 1938, Professor Leon Theremin vanished. The controversy over his disappearance has never been satisfactorily resolved, as some say he was kidnapped from his New York apartment by the NKVD (an earlier incarnation of the KGB) and others insist he left the U.S. because of financial difficulties. It seems clear, however, that upon his return to Russia, he was indeed imprisoned in a Siberian gulag by Stalin. Theremin was then relocated to a secret research lab, where he developed electronic espionage devices. He was finally released in 1947, but continued to work as a researcher for the KGB. In 1964, he became a professor of acoustics at the Moscow Conservatory.

Communications of the day not being what they are today–the Cold War notwithstanding–no one had heard hide nor hair of the good Professor for almost thirty years, until the U.S. correspondent Harold Schonberg spotted him while on assignment in Moscow in 1967. As a result of Schonberg's article in the New York Times, Theremin was dismissed from the Conservatory, whose Dean didn’t want to be associated with electronic music. The news that Professor Theremin had re-surfaced was a welcome shock to the West, however. Since the Professor's disappearance, the era of electronic music he had brought forth had been growing, and mutating. His monster machine attached itself to popular consciousness via soundtracks to films like The Day the Earth Stood Still, The Lost Weekend, and Spellbound.

In the hands of Clara Rockmore, the theremin was a gorgeous and otherworldly Classical instrument used most effectively in slower, legato pieces like Saint-Saëns' The Swan. But the instrument's haunting timbre–at times stringlike, at times voicelike–and gliding articulation also made it the go-to axe for creators of science fiction soundtracks.

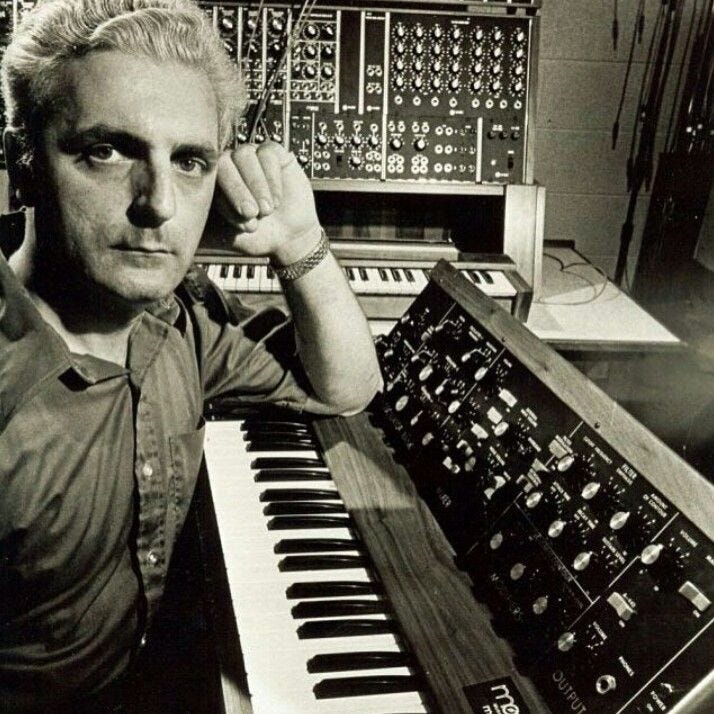

In the meantime, a fourteen year old inventor named Robert Moog began building theremins (they can be built from kits that are still sold today). His name became forever associated, however, with yet another new instrument: the synthesizer. The original Moog Synthesizer was to today's synths as Frankenstein's monster was to Hal, the supercomputer in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Huge consoles with rows of inputs and outputs connected by patch cords, they were machines designed to take sound apart and put it back together any way you wanted.

Robert Moog

Despite being an electronics innovator, Moog was a nature lover who adored gardening and being outdoors, eventually moving his family to a farm outside of Asheville, North Carolina.

The name Robert Moog is still revered amongst today’s electronic musicians. But Moog actually lost the legal right to use his own name in his products after he left Moog Music, which had become a “toxic corporate culture.” After years of legal battles Moog’s ability to use his name was restored, but it took its toll on his health and finances.

In the mid 1980's, I studied Moog synthesizers in a class taught by the late Lefferts Brown in his studio on Canal Street. The space was more like a mad musical scientist's lab than a conventional studio. Instead of your typical piano, drum set, amps and mics, it was packed with all these Moog and Arp synths. With them you could actually make your own sound waves from scratch. Spice 'em with sawtooths, squares and triangles, fry 'em with filters, then serve up some shaw 'nuff crazy chord cuisine! Music had stuck its finger in the toaster, and it would never be the same again. But synth music was missing one important ingredient: an artist who could legitimize it, make it accessible and commercial, make it nice. Enter Walter Carlos.

In 1968, Carlos made an album called Switched-On Bach–compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach performed on the synth. SOB, as it came to be known, immediately sold a half million copies and made Carlos a celebrity. Fame came with a price, however. As Carlos' career blossomed, the world demanded to know how it was that Walter Carlos of the first albums and Wendy Carlos of the later albums were one and the same person. In a famous Playboy Magazine interview, Wendy Carlos told the full story of her childhood as a secret cross dresser who always felt like a girl in a boy's body. Inspired by the stories of Renee Richards and Christine Jorgensen, Carlos decided to undergo a sex change operation.

Though this period for Carlos was not without its complications, she never regretted making the dramatic decision to [literally] re-invent herself. She remains a well-respected composer today by virtue of a career move that solidified her reputation: In 1972, Carlos' producer and friend Rachel Elkind had heard that Stanley Kubrick was directing a new film. Being Kubrick fans and intuiting that Carlos' music would be just right for the project, they contacted Kubrick's agent and offered to send samples. Days later, Carlos and Elkind were on their way to London to plan the soundtrack for A Clockwork Orange.

Wendy Carlos

CUE THEREMIN MUSIC–Cut to Professor Leon Theremin, returning to the United States in 1991 for a visit. Finally freed from the steel grip of the Iron Curtain, he spoke candidly with Steven Martin about his incarceration in Russia, in Martin's 1993 documentary Theremin: An Electronic Odyssey. Professor Theremin died in Moscow the day after the film's debut in Great Britain.

As often happens in the families of musicians, the lineage continues with Leon Theremin’s great-grandson Peter Theremin, who composes and performs on the instrument. He is also the founder of a theremin school, and lectures widely on the subject.

You can be sure that interest in this unusual and difficult instrument has not waned over the years. Should you wish to learn how to play it, inexpensive kits are available, as well as pre-assembled units.

If Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk were bebop's Holy Trinity, then Theremin, Moog and Carlos were no less in the world of electronic music. Figures like these remind us, in our era of "multi-culti" education, that art is not created by cultures but by individuals. So let us not dim the bulbs of our future Birds, Dizzys, Moogs and Carloses. Let's allow them to shine, and the resulting glow will illuminate the path before us.

Wonderful story Su! Ha, I'm currently reading the Trout Mask Replica, part of the 33 1/3 series by Kevin Courrier, and the use of the Theremin was just detailed in its unique usage on the album, Safe As Milk. I enjoy your writing and stories! Keep it up please, and good day madame.

US Conductors, 2014, a fictional acct. of Leon Theremin and Ms. Clara. A mixture of fact and fiction and a nice read.

In high school there was a composer who had a Theremin and would occasionally bring it to school to play for us. A fascinating instrument.